15 Mental Models I Keep Coming Back To : 1 of 15

1 out of 159

This newsletter has always been a bit messy in a good way. Notes, ideas, investing thoughts, mental detours that felt worth writing down at the time.

But every now and then, it feels useful to add a little order to the chaos. Last year, I started to write a series about fifty books that stayed with me, and I’ve been really enjoying the process. It’s been slower than expected, more reflective than planned, and I suspect it’ll quietly stretch across a decade, and I am perfectly okay with that.

I felt like trying something similar again.

This is going to be a series on mental models. Fifteen of them. Not because they are definitive or original, but because they have been useful. Some help simplify complex decisions. Some act as filters. Some are reminders of how easily we can fool ourselves.

There is no particular order and no finish line in sight.

Just one mental model at a time.

Here is 1 out of 15.

Ergodicity

Ergodicity is one of those concepts that feels abstract until it hits you in real life: what’s true for a group isn’t necessarily true for an individual.

Imagine a casino. 100 people walk in for a day of Roulette. Five of them go bust. You might be tempted to say, “Ah, the probability of going bust is around 5%.” Sounds reassuring, right?

Now imagine one person goes to the casino for a hundred days. The odds are much worse, in fact, unless they get incredibly lucky, they’ll likely go bust long before the 100th day. That 5% daily probability for the group does not translate into the probability for one person over many trials.

This is the essence of ergodicity: a system is ergodic if the expected value of a process over time for one individual is the same as the expected value across a group at a single moment. Most things in life are not ergodic. Treating them as if they are is where people get into trouble.

The definition sounds abstract, but it shows up in very ordinary places. Investing is one of them. Imagine you’re handed a list of annual returns. Nothing exotic. Just ten numbers. Some good years, some bad ones, a couple of disasters, a couple of bangers.

+10.51%

+8.75%

+19.42%

+4.32%

+24.12%

−51.79%

+54.77%

+39.83%

−24.62%

+17.95%

Now imagine three parallel universes.

In Universe A, these returns arrive exactly in the order you saw them.

In Universe B, all the bad years get out of the way first and the good years come later.

In Universe C, you get the good years upfront and the bad ones at the end. Same returns. Same years. Just rearranged.

Here’s the deceptively simple question.

Does the order of returns matter?

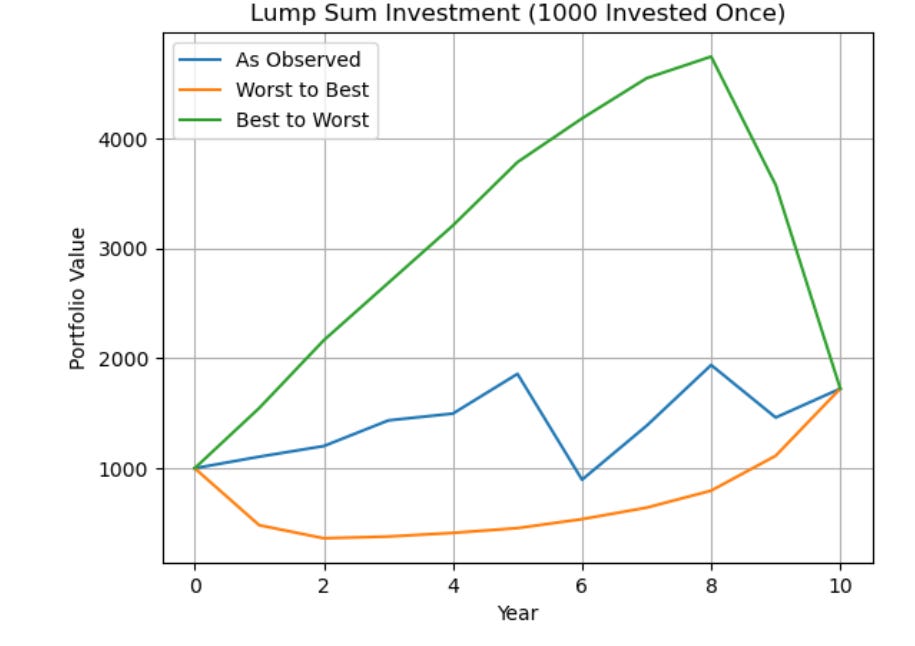

Case 1 - Lump sum

You invest 1000 once. You do nothing else. You sit on your hands and let compounding do its thing. Run the math. Whether the worst year happens first or last doesn’t change the final number. The multiplication of returns is commutative. The path might feel very different emotionally, but mathematically, it lands you in the same place. This is an example of an ergodic outcome.

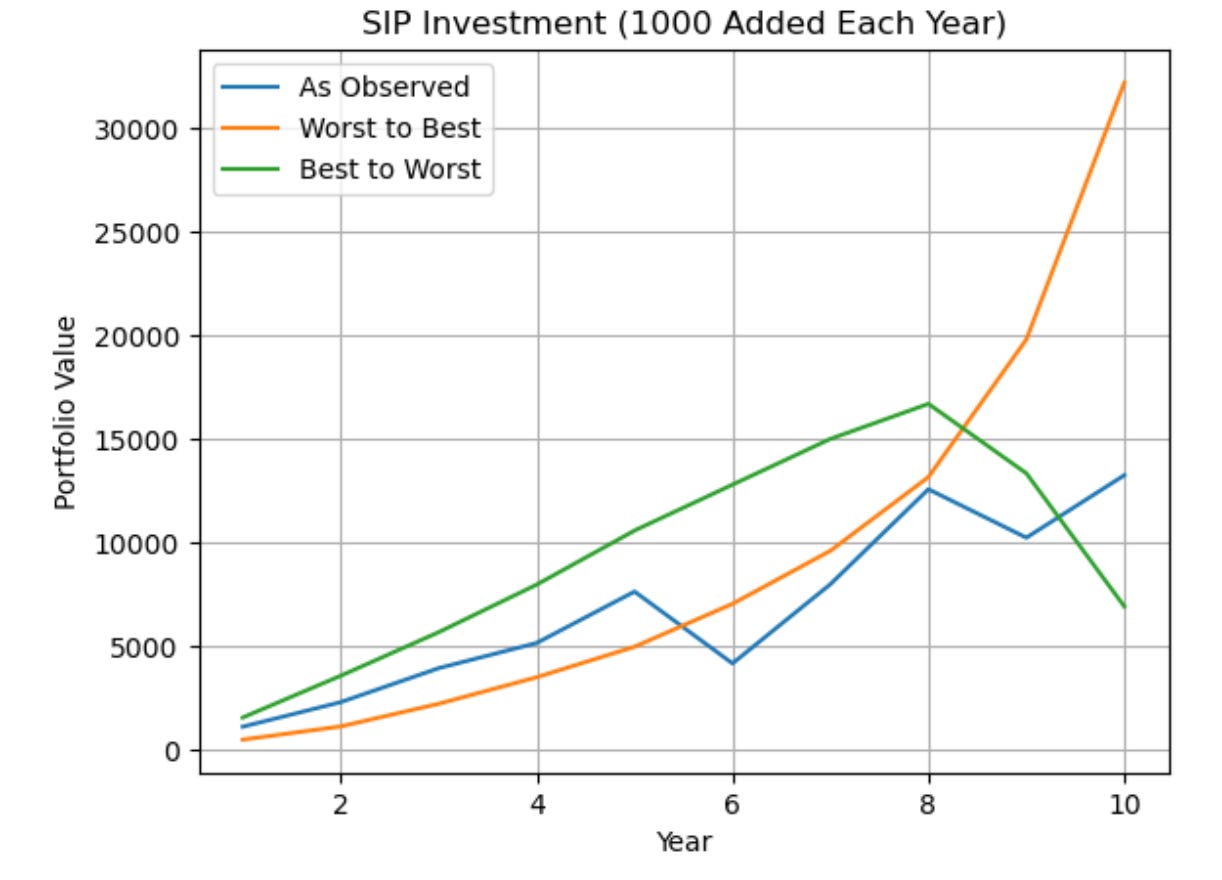

Case 2 - Annual Investment (SIP)

Now we change one thing. Instead of investing once, you invest 1000 every year. Same returns. Same three universes. Now run the math again.

Suddenly, the ending balances are wildly different. If bad returns come early, your later contributions benefit from recoveries. If bad returns come late, they crush a much larger capital base. Same returns. Same behavior. Completely different outcomes.

The path matters.

Once you see it in investing, you start seeing it everywhere.

Take health. Smoking a cigarette today doesn’t do much. Smoking one tomorrow doesn’t either. Look at it across a group and at a single moment in time and you might conclude that the damage is marginal. Plenty of people smoke and seem fine. The expected outcome doesn’t look catastrophic.

But health isn’t experienced as a group average. It’s experienced as a path.

The harm compounds quietly. One person smoking for thirty years is not the same as thirty people smoking for one year each. Health is deeply non ergodic. Small, repeated exposures accumulate until they don’t. The same logic applies to sleep, diet, exercise, stress.

And then there’s risk.

In non ergodic systems, survival comes before optimization. You don’t get rewarded for having a high expected return if you don’t make it to the next round. This is why leverage is dangerous even when it looks attractive on paper.

Buffett intuitively understands this when he says “To succeed, you must first survive.”

Nassim Taleb has been circling this idea for years, often without using the word itself. His obsession with fragility, ruin, and survival all links to this. Ole Peters approaches it from the other direction, putting math around something people like Buffett and Munger seemed to grasp intuitively: that time changes the rules of the game.

The common thread is simple. You don’t experience life as an average. You experience it as a sequence. If this mental model does nothing else, let it remind you to respect the sequence, not just the destination. Think about the path. You only get one.

If you are still reading, thank you! Appreciate the support.

Cover image taken from Unsplash

This breakdown of ergodicity through the lump sum vs SIP comparison is brilliant. The idea that sequence risk only matters when you're actively contributing really clarifies why timing feels so different for accumlators vs retirees. I've been dollar-cost averaging for years without fully understanding why early volatility actualy helps me, and this framework nails it. The health analogy also lands perfectly.