How I look at valuation now

A game of belief and reverse DCFs

Okay, just to be clear, I love valuation, but I’m far from an expert. The deeper I dive into it, the more I realize how difficult it is to pin down a price with any real certainty. It’s one of those topics where, no matter how much you think you understand, there’s always a moment when you stop and go, Wait, what am I missing? So, consider these thoughts more of a journal entry rather than a final, concrete take.

To me, equity valuation is largely about understanding the gap between what I believe and what the market is assuming. Maybe I expect higher growth, have a more pessimistic view of a company’s scalability, or simply put more (or less) faith in management than the market does. The key takeaway is that valuation, and by extension investing, comes down to believing in something the market hasn’t fully priced in yet and acting on it before everyone else catches on.

Now, figuring out what the market is assuming requires a few different approaches. You can ask around, talk to the right people, check Bloomberg estimates, or even run a Reverse Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis. I’ll dive into Reverse DCFs in a bit.

But first, let’s quickly touch on what most people on the street do when valuing a company. The process is pretty straightforward:

Estimate earnings for the next couple of years, usually based on management guidance, financial models, or available forecasts.

Apply a multiple to those earnings like a price-to-earnings (PE) ratio—to get a valuation. The multiple might be based on historical trends, future expectations, or simply the analyst’s preferred method.

Now, let’s talk about Reverse DCFs.

A Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) valuation estimates a firm’s future dividends or free cash flows and discounts them back to the present value based on risk. A Reverse DCF flips this idea on its head. Instead of figuring out what a firm should be worth, you assume the current stock price is correct and work backward. In other words, you tweak assumptions—growth rate, return on equity (ROE), cost of capital, etc.—until your DCF model aligns with the market price.

Why do this? A Reverse DCF tells you what the market is implicitly assuming about a company to justify its current price.

Since many investors think in multiples, I really like the idea of using an intrinsic PE ratio to run a reverse DCF. Confused?

Here’s how that works. We start with the one-stage dividend discount model.

It becomes clear that the price-to-earnings (PE) ratio depends on three crucial factors:

Growth rate

Dividend payout ratio (which is a function of Return on equity and growth)

Cost of capital (discount rate)

It’s a straightforward relationship, but it shows how these factors drive a company’s valuation.

This formula works well for a simple, one-stage model where growth is constant. But what if we have a company that grows in two stages—let's say it has a high growth phase initially, followed by a slower, stable growth phase? The math gets slightly more complicated.

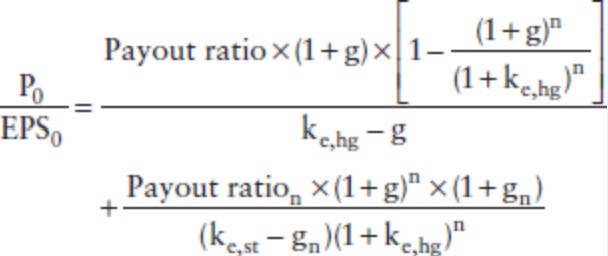

Fortunately, Aswath Damodaran, a professor at NYU, provides a formula for this in his brilliant book Investment Valuation.

where

g = Growth rate in the high growth period

ke,hg = Cost of equity in high growth period

ke,st = Cost of equity in stable growth period

Payout = Payout ratio in the first n years

gn = Growth rate after n years, forever (stable growth rate)

Payoutn = Payout ratio after n years for the stable firm

And you are almost done. I plugged this formula into Excel and I think I have basically set up a simple tool to try to estimate what the market is assuming about a company.

As an example, let’s take a company like Asian Paints.

It's been a market darling for years, consistently growing and outperforming expectations. However, in recent times, it’s faced new competition and, as a result, has fallen quite a bit from its peak. As of 30th January, 2025 it is trading close to 2250 with a trailing PE of 46. (Screener.in)

So, what do I need to assume to match current valuations?

One way to make sense of this valuation is to assume the following:

15.5% after-tax profit growth for 15 years, after which growth is 6.5% for perpetuity.

A 43% payout ratio during that period

A cost of equity at 11% which drops to 10% in perpetuity.

Now, the question is: are these assumptions realistic?

Over the past nine years, Asian Paints has grown its profits by 16% annually (CAGR), so the growth assumption isn’t unprecedented. But is it repeatable? That’s where things get tricky. The market dynamics today are different from what they were a decade ago, and sustaining such growth becomes harder as a company grows in scale. Industries mature, competition intensifies, and growth typically slows over time.

On top of that, an 11% cost of equity seems quite low, in my opinion, given the risks of maintaining such ambitious growth targets.

So, even though Asian Paints has a strong track record and has already dropped quite a bit from its peak, I find it hard to get comfortable with its current valuation. The assumptions required to justify its price are incredibly demanding and rare to sustain over such a long period.

Of course, you might see things differently, and that’s the beauty of valuation. It’s all about believing in something the market might not yet see, and in this case, you may have a more optimistic view than I do. And that’s perfectly fine. Different perspectives are what make markets and valuation so dynamic.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you. I really appreciate you spending some of your time on a topic that’s often considered pretty boring by most people.

Disclaimer: This is not investment advice. The content here is intended to be informative and educational, based on my own thoughts and analysis. While I’ve tried to be as accurate as possible, I can’t be held liable for any decisions made based on this information. Always do your own research or consult a professional before making any investment decisions.