Mental Models for investors

Mental Models Mania

Like almost everyone else on planet Earth, I too first heard of mental models thanks to legendary investor Charlie Munger.

“Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience both vicarious and direct on this latticework of models.”

The idea of having a toolkit of ideas and concepts that may further refine our thinking and in turn decisions was groundbreaking, to say the least. I started to think of mental models as a cheat sheet that many of us might have made for an exam. I usually filled mine with formulas and then my job in the exam was to make sure I picked the right formula. Mental models, in my opinion, work the same way but are not restricted to an exam.

Reading a fair share of/about Munger, Taleb, Kahneman, Peter Bevelin, Moubaussin, etc, only got me more involved in this journey of creating a “latticework of mental models”.

This article is an attempt to mention a few mental models while touching on their investing significance. Ofcourse these models are useful outside the world of investing but for now, I try sticking to their investing significance.

Without any further ado, let’s get to it.

1. Inversion

Inversion involves thinking backward rather than forwards. Instead of trying to solve the problem, you try to think of anything you can do that will not help you solve the problem.

So instead of asking “Which restaurant do you want to go to” ask the question “Which restaurant do you not want to go to.” In the investing context, Warren Buffett says, “The first rule of investment is, “Never to lose money. The second rule is, Never forget Rule 1.”

His rule is not about some positive idea to generate excess returns. It’s actually about not losing money. It’s inverting the problem. As his partner in crime Charlie Munger says, It’s about avoiding stupidity rather than seeking genius.

One of the most significant applications of inversion in investing can be seen in Reverse DCFs. Instead of trying to value a company, you try to figure out what assumptions need to be made to arrive at the current market value of the company. For more on Reverse DCFs, it may be worth reading “Expectation Investing” by Michael J. Mauboussin.

2. Compounding

Founder of Microsoft, Bill Gates once said “Most people overestimate what they can achieve in a year and underestimate what they can achieve in ten years”. This quote basically touches on our inability to understand exponential growth and our tendency to focus on instant gratification.

In the investing world, we often fail to understand the power of compounding. It’s easy to understand the impact of 20% returns for 1 year but understanding 20% for 20 straight years is where we make a mistake.

3. Feynman technique

Richard Feynman was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in 1965 for his work in quantum electrodynamics. Feynman could brilliantly convey complex ideas in simple words and the Feynman technique is all about that. It is about identifying a topic or a problem and simplifying it so that we can actually teach it to a child. This works because when we are unsure about something, we often automatically use complicated words or jargon, to hide our lack of knowledge. Trying to explain it to a child helps us find gaps and holes in our own understanding of that topic. While that sounds simple, Feynman’s technique is a super powerful tool because it suddenly makes you realize that you may not know certain topics in the detail that you had thought earlier.

A quick thing I would like to add here is the conversion of units into more understandable metrics. We often measure things using units like square kilometers, joules, trillions, etc. Unfortunately in the process of using these units, the essence may be lost. Often converting these units to more understandable units can help.

For instance, to get an idea about just how large a “trillion” is, it can be useful to convert it to seconds. A million seconds is 12 days. A billion seconds is 31 years. A trillion seconds is 31,688 years.

4. Thinking from First Principles

Elon Musk beautifully broke down the idea of first principle thinking when he said “It involves boiling things down to their fundamental truths and reason up from there, as opposed to reasoning by analogy”.

First-principle thinking can often be thought of as starting from scratch. You try to separate the underlying ideas from any assumptions based on those ideas to get a clearer picture. In the video above, Elon touches on how the common consensus view was that battery packs were expensive and had remained expensive for many years. However, when thinking from first principles you question that view and start asking questions like –

Why have battery packs been so expensive?

What are the material constituents of the batteries?

What is the stock market value of the material constituents?

If one bought the materials on the London Metal Exchange what would each of those things cost?

When asked about risk in Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meetings, Warren Buffett did not talk about beta or standard deviation. He said “ We think of business risk in terms of what can happen — say five, 10, 15 years from now — that will destroy, or modify, or reduce the economic strengths that we perceive currently exist in a business. He boiled it down to a basic assumption and worked up from it.

5. Illusory Correlation

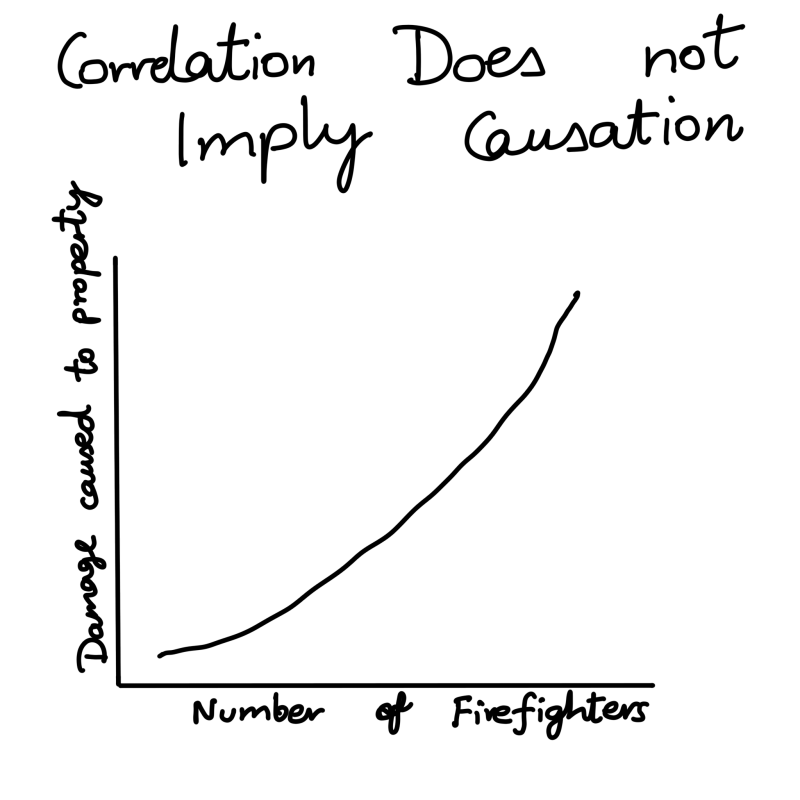

You may have heard the popular saying, “Correlation does not imply causation”. Simply put just because two things happen together does not mean that one caused the other. I like to split it into four different cases.

X caused Y.

Y caused X.

X and Y did not cause each other. They both may be linked to a third variable like “Z”.

Just a random coincidence.

As the image above shows, you could show a positive relation between damage to a property and the number of firefighters that went to the property. However, that does not imply that one caused another. Ofcourse in this case the severity of the fire is the third variable that is responsible for the same.

Illusory correlation is a huge problem in the financial markets because we are constantly bombarded by news that is trying to make sense of movements in the markets. “The market is down because _________. “

Without statistical evidence, we may often be mistaking correlation for causation. For more on this, you could refer to this article.

6. Inattentional Blindness

In the 1990s, Harvard psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris filmed two teams of students passing basketballs to each other. One team wore black T-shirts and the other wore white. In the middle of the video, a student dressed as a gorilla walked into the center of the room, pounded his chest, and walked out.

The psychologists then conducted an experiment where they made people watch this video and asked them to count how many times the players in white T-shirts passed the ball. At the end of the video, the viewers are asked if they noticed anything peculiar. Surprisingly, close to 50% of the viewers missed the gorilla.

Apart from highlighting our inability to multitask efficiently, the experiment touched on our tendency to miss something obvious which is right in front of us, simply because we don’t expect it to be there. Psychologists Arien Mack and Irvin Rock termed this phenomenon as inattentional blindness.

When watching the video we don’t expect a random man dressed as a Gorilla to walk in a video where we are instructed to count the number of ball passes. In the movie Hangover, there is a scene where Alan walks into the washroom to take a leak. As he is doing so, he looks to the right and sees a tiger. He carries on urinating for a couple of seconds until he realizes what he just saw. He then proceeds to run out of the bathroom screaming. I know it’s fiction but that pause before panic may actually be explainable. (It’s probably a stretch but you get the idea)

Inattentional blindness can have huge repercussions in the investing world. Often it is a reminder that we can often miss something obvious if we don’t expect it to be there. This is where the next mental model on this list may come in handy.

7. Checklists

In his brilliant book “Checklist Manifesto”, Harvard Professor and surgeon Atul Gawande mentioned that despite all the complexity that surgery may require, small details like not washing your hands, not giving antibiotics at the right time, etc can be costly. He then talked about how having a succinct two-minute checklist actually helped reduce death in surgery. When surgeons with years and years of practice resort to checklists, it only makes sense that investors with far less practice in a field with far more luck, also resort to a checklist. Investing checklists don’t need to be revolutionary but they should ensure that we are not missing something obvious!

8. Survivorship Bias

Survivorship bias is a common error that occurs when we assume that success tells us the whole story. We fail to account for failures, often due to their lack of visibility. We use success stories as an example of “all the stories” and come to the wrong conclusions.

Every football fan during the transfer season is busy on youtube to find out which player his/her team has signed. We forget that youtube videos are meant to showcase the best plays and highlights of a player. We don’t see the bad moments and come to faulty conclusions.

In the financial markets, we often make decisions on published fund data. Unfortunately, this published fund data does not factor in the funds which have gone bust. This skews the data and hence our decision-making. We need to remember that we may not be seeing the complete picture!

9. Pavlovian Association

The Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov studied the digestive system of dogs. In one experiment he rang a bell just before giving food to the dog. He repeated this several times until the dog salivated at the sound of the bell alone. The dog’s brain started expecting food merely by the sound of the bell. The presence of food was not required anymore.

Conditioning can often lead to a particular reaction to a stimulus. For instance, during bear markets, we are often primed to hear bad news and hence can sometimes miss obvious signs of better times ahead. That’s what makes contrarian bets difficult.

10. Moats

The term Moat is often overused in an investing context. To add some order to the chaos, I like to use Hamilton Helmer’s framework. He breaks down Moats into seven categories. -

Brand

Switching Cost

Scale

Counter Positioning

Network Effects

Cornered Resource

Process Power

I have co-written an extensive article on the same here.

11. Ergodicity

If 100 people go to a casino for a day and 1 out of those 100 people, goes bust, we can conclude that the probability of going bust in the casino in a day is 1%. On the other hand, if 1 person goes to the casino 100 times, he will definitely go bust. The probability of one person going bust if he plays 100 times is 100%.

What’s interesting here is you cannot apply that 1% group probability to the individual time probability.

A system is said to be ergodic if the expected value of an activity performed by a group is the same as for an individual carrying out the same action over time. That is not the case for the example above. Most things in life are not ergodic and so thinking that they are is where the problem lies. Fund Manager Juan Torres Rodriguez and Andrew Evans explain the concept beautifully in this article.

12. Porter’s Five Forces

While not an exact “Mental model”, Porter’s Five Forces is a framework that can be used to better understand a particular industry and company. When trying to analyze a company or an industry it makes sense to try to break it down in the format below.

The threat of new entrants

Threat of substitutes

Bargaining power of customers

Bargaining power of suppliers

Competitive rivalry.

If nothing else, it helps you get more clarity on your thoughts about the industry. For instance, have co-written this article where we leverage Porter’s Five Forces to write on the Indian Spirit industry.

13. Critical Mass

In nuclear physics, critical mass can be defined as the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. (Really wish I studied Physics better!) Adopted to other fields, critical mass is often thought of as the tipping point which when achieved by a firm/product changes the behavior of the system dramatically.

A lot changes from 1 degree to 0 degrees for water. On the surface, it’s only one degree but the change in form is drastic. In finance, think about economies of scale.

14. Theory of Reflexivity

Popularized by George Soros, the theory of reflexivity theory states that investors don’t base their decisions on reality, but rather on their perceptions of reality instead. The actions they take according to their perceptions of reality have an impact on reality itself which then impacts their perception. It’s a 2-way feedback loop. This theory opposed a lot of theories including the efficient market hypothesis.

15. Cobra Effect

At some point, while ruling over India, the British were concerned about the ever-increasing Cobra population. To try to reduce it they decided to introduce an incentive. A person would be rewarded for every dead cobra that they brought. This worked wonderfully for a while until the British realized that people had started breeding and killing cobras. When they removed this incentive, people let the Cobras free leading to a further increase in the Cobra population.

Their incentive had created a further problem. As Peter Bevelin writes “Actions have consequences and consequences have further effects”.

I studied in a school that prioritized academics over everything meant that every opportunity to play some football(soccer) was capitalized. In around 9th grade, around 20 of us would finish lunch in 5 minutes and spend the remaining lunch break playing football. As the football field was occupied, we would start playing wherever we could. While that was not a problem to us, it was problematic as children in 2nd and 3rd grade also had their break at the same time and so they could easily get hurt due to our footballing endeavors. The teachers eventually intervened and forbade us from getting access to footballs during lunch.

Of course, as teenagers, there was no way we were going to accept this. Innovation(word used loosely) took over as we discovered the beauty of foil paper. Foil crumbled into spheres with around three-four layers of scotch tape actually served as a suitable replacement for a ball. While these balls could only last around 3-4 lunch breaks, that was enough for us. Soon enough many of us started making these balls at home and getting them to school. The quality of the tape and the quantity of foil used all played a part. Dare I say, it was an art. These foil footballs were smaller than actual footballs but that only improved our skill. So much so that one of my batchmates ended up representing India and credited foil football to his development as a player. Okay, that last part is not true, but it’s fair to say that foil football had taken over. At least until that too was eventually banned.

As I said, Actions often tend to have unintended consequences As investors it is often easy to think about the first-order effect but it is in fact the second and third-order effects worth pondering over. Howard Mark talks about the same in great detail in his books.

16. Information Asymmetry

When one party knows more about a product/service than the other party, there is asymmetric information. The most common example of the same can be seen in the market for used cars or phones. The seller has more information and the advantage and hence can often hide stuff from buyers. This often leads to buyers being extra cautious and so the price drops. Hence in the 2nd car market, often some cars could actually be in really good condition but are being sold at a very low price simply due to the problems which information asymmetry creates. Warranties, 3rd party quality checks, etc are some potential solutions to this problem.

I suppose investing is all about asymmetric information. As an investor, you are constantly taking the call that you may know something that the market does not. It all comes down to how correct you are!

17. Hindsight Bias

Apart from helping people connect and aggregating data for targeted advertising, I was confident that Facebook’s greatest gift to the world was its birthday reminders. That was until I went back and looked at some of my older status updates.

“Can someone please send me an Olive tree on Farmville!”

“Lampard. What a goal Wow!”

Facebook’s greatest achievement is to remind you of what a moron you were five-ten years ago. I had this vague impression of me being a ” somewhat cool kid” which vaporized due to the anecdotal evidence that was found on Facebook. While unfortunate in the scheme of things, this very evidence acts as a reminder of what I was thinking of when I was seven or thirteen. It’s a superpower in a way as it allowed me to travel back in time. It’s something that every investor and trader needs.

Once we know how something happens it’s almost impossible to go back in time and understand what we were thinking before the event. Our brain almost automatically weaves a narrative to explain what just happened. This is scary as it allows us to convince ourselves that “we knew it would happen before it even happened”.

Hindsight bias prevents us from learning from our mistakes and successes as we may claim that we always knew it along. A simple solution is to keep a journal so that we can actually go back and see what our thought process was. Keeping an investing journal and recording our thoughts before making an investment is actually a superpower as it allows us to travel back in time and better understand where we potentially went wrong, without falling for hindsight bias.

18. Luck Vs Skill

Most activities in life involve some amount of luck and skill. Mistaking luck for skill is where the problems begin. Different activities have different levels of luck involved in them. A quick way to identify the role luck plays in an activity is to see if you can purposely lose in an activity,

For instance –

A dentist can purposely make mistakes in his/her job and so it’s largely a skilled activity.

An investor in the short run may find it difficult to purposely lose money. It’s a good mix of skill and luck.

Snakes and Ladders is luck as you cannot purposely lose. It’s all on the dice.

It’s important to factor in randomness and not come to faulty conclusions immediately. Nassim Taleb touches on this in his brilliant book “Fooled by Randomness”. You can also read up more on this in Michael Mauboussin’s book Success Equation.

19. Regression to the mean

Regression to the mean says that for any series of events where some amount of chance is involved, very good or bad performances, tend on average, be followed by more average performances or less extreme performances.

Basically, if we do extremely well, we are likely to do worse the next time, while if we do poorly, we are more likely to do better the next time. Regression to the mean is not a natural law. but a statistical tendency.

20. Skin in the game

This is probably the simplest yet most important mental model on this list. Asking a barber if you need a haircut is probably not the smartest idea as you are not factoring in the barber’s incentives. Whenever we take advice or give any instructions we always need to factor in the incentive that the person giving the advice may have.

As Nassim Taleb brilliantly says, “Don’t tell me what you think, tell me what you have in your portfolio”. Sebi interestingly has incorporated some of this as people running a mutual fund have to by law put a certain percentage of their salary directly into that fund. When looking directly at companies, it is always interesting to see the promoter shareholding and how it has changed over time.

21. Opportunity Cost

Opportunity cost is the cost of the next best alternative while making any decision. It basically involves asking the question “What am I giving up by doing this specific thing?”

For instance, if you go to a movie for 3 hours, the opportunity cost could be whatever you could have done in that 3 hours. Work out, eat, sleep, etc. Considering opportunity costs can often help us make better decisions.

In the investing world, I believe that the “Cost of Equity” can often be thought of as an opportunity cost.

22. Circle of Competence

Circle of competence is all about sticking to what we are good at. While that sounds simple, we first need to know what we are actually good at. Mental models like First Principles, Inversion, and Feynman technique all come in handy here. Warren Buffett divides his investing universe into three buckets. –

Yes

No

Too tough.

The whole idea of having a too tough category is so that he does not venture outside his area of expertise. Of course, over time we want to widen our circle but the core idea is to make sure we stick to it.

23. Pareto Principle

Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto once noted that 20% of the pea pods in his garden were responsible for 80% of the peas. He expanded this principle to macroeconomics by showing how 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. The Pareto principle states that for many outcomes roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of the causes. If we translate this principle to investing, it would mean that often 80% of the profits come from only 20% of the trades we make in our portfolio.

If you made it so far, thank you. I will continue to update this post over time. Subscribe, if you have not yet!

Please do an entire piece on inversion!!!

super helpful piece!