Popcorn, Planes, and Poor Returns

Some businesses just can’t catch a break. No matter how big the market, how strong the demand, or how beloved the product, they somehow end up with a reputation for being terrible investments. Airlines and movie theatres sit high on that list. And while I love a good flight and an overpriced bucket of popcorn as much as the next person, there’s a reason the market doesn’t always share that enthusiasm. Let’s dig in.

Disclaimer: This article is intended solely for informational and educational purposes. It does not constitute investment advice, a recommendation, or an offer to buy or sell any securities.

Airlines

From Jet Airways and Kingfisher to Pan Am and Trans World Airlines, the list of carriers that have taken off and crashed, metaphorically, is a long one. Airlines are notorious for their boom-and-bust cycles, often driven by factors that are completely out of their control: oil prices, pandemics, geopolitics, currency swings… you name it.

Warren Buffett once famously called airlines a “death trap for investors.” And yet, years later, he went against his own advice, buying sizable stakes in several major U.S. carriers. There was logic to it: the number of players had consolidated, pricing discipline had improved, and the industry seemed to have finally grown up. For a moment, it looked like airlines might actually become investable. Then COVID hit. Global travel ground to a halt, and just like that, Buffett pulled the plug — exiting his airline positions at a loss.

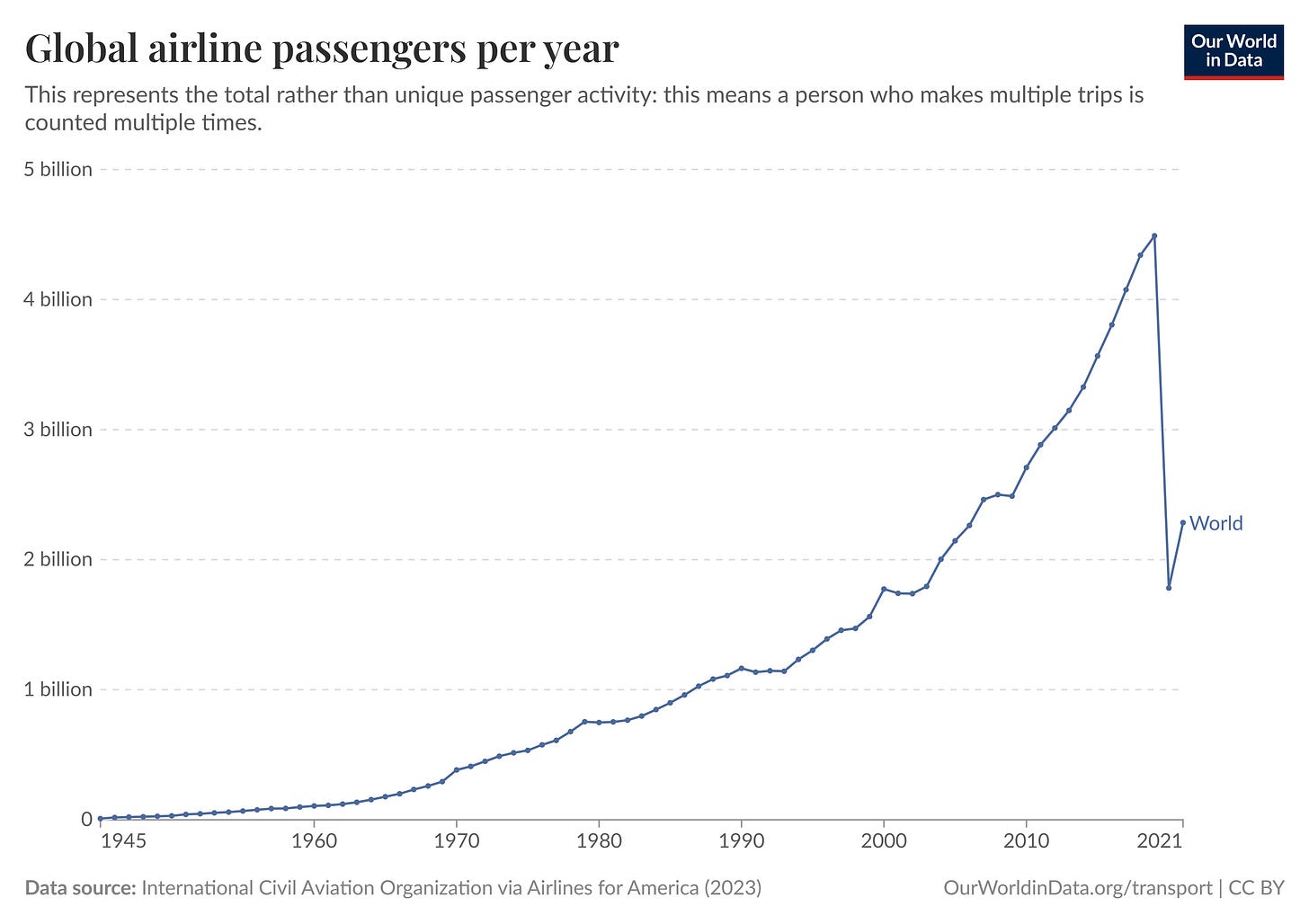

Now, it’s tempting to think: “But air travel is booming. Airports are crowded. People are flying more than ever.” And you'd be absolutely right. Demand for air travel has consistently grown over the years.

The problem? Airlines have rarely captured that value in the past. Michael Mauboussin touches on this briefly in his classic Measuring the Moat.

One chart in particular stands out: the ROIC minus WACC spread across the entire aviation industry. It serves as a quick and brutal reminder of how poorly the airline and airport sectors, on average, have performed in creating real economic value. Of course, there are outliers. But the overall picture is far from encouraging.

One such outlier in India has been InterGlobe Aviation. In fact, it is one of the largest airlines in the world by market capitalization. While I cannot point to one single factor behind its success, here are a few potential reasons.

Massive Initial bulk order & single‑type fleet

In its very first year of operations, IndiGo stunned the industry by placing a firm order for 100 Airbus A320‑200 aircraft. By committing to one aircraft family in such volume, the airline not only secured steep list‑price discounts, but also set the stage for a single‑type fleet. That meant pilots, cabin crew, and mechanics all trained on the exact same aircraft, slashing training time and costs, simplifying scheduling, and reducing spare‑parts inventories across the board.Strategic Sale‑and‑Leaseback (SLB) Model

In a sale‑and‑leaseback arrangement, IndiGo initially purchases new aircraft at favorable prices, then immediately sells them to a lessor, often locking in a profit, and leases them back for its own operations. This approach allows for a relatively asset light approach. Moreover, by continually adding newer aircraft through SLBs, IndiGo keeps its maintenance costs competitive, as newer aircrafts tend to have lower operational costs.Strict cost control

Low cost carriers have generally fared better than their full-service counterparts across the globe, and IndiGo is a strong example of that trend. While peers like Kingfisher were focused on offering freebies and turning air travel into a luxury experience, IndiGo took a more disciplined approach, prioritizing efficiency and cost control from day one. The airline maintained a lean structure, with fewer staff members taking on multiple roles. Everything from in-flight services to operational processes was designed to minimize expenses without compromising on reliability.

Despite doing exceptionally well by airline standards, even IndiGo isn’t immune to the brutal economics of aviation. The nature of the sector makes consistent profitability a constant battle, not a guarantee. Case in point: in October 2024, IndiGo shocked the industry with a ₹989 crore loss in Q2.

The airline had around 70 planes grounded due to engine issues with Pratt & Whitney. To cover this gap, IndiGo had to lease aircraft at short notice, pushing lease expenses up.

Furthermore IndiGo’s CASK (Cost per Available Seat Kilometer), excluding fuel and forex impact, rose by 23% year-over-year, driven primarily by AOG-related costs (aircraft on ground) and broader inflationary pressures.

This serves as a sharp reminder: in aviation, costs are volatile, margins are razor thin, and even the best run airlines can have bad quarters due to external shocks. I generally do not love the sector, largely because we seem to be living in a world where external shocks are becoming the norm. Whether it is tariffs, pandemics, or something else entirely, these disruptions are frequent and hard to predict.

And with pandemics in particular, as global travel increases, urbanization accelerates, and ecosystems are disrupted, the odds of encountering another one are not going down. All this to say, airlines cannot treat pandemics as rare Black Swan events. They are very real and recurring risks that the industry must contend with.

Still, in many ways, I prefer this sector to theatres, mainly because of the organic growth the industry is poised to experience. And when we talk about India, the aviation industry is still in its infancy.

Movie Theaters

When we think about crucial variables for theatres, it really boils down to two things: occupancy rate and average spend per head .

In simple terms, how many people are showing up, and how much are they spending once they’re there? Sounds straightforward enough, but in reality, both of these are notoriously hard to control. And that’s where the business model starts to get tricky.

No Control on Demand

Imagine being a theatre owner who’s done everything right. You’ve got comfortable reclining seats, top-notch sound, good food, etc. But here's the kicker: you have zero say in the quality of the films being released. If the studios serve up a dud (or a string of them), you’re stuck with half-empty halls and disappointed customers. You're at the mercy of someone else’s creative and commercial decisions.The Rise of OTT

These days, people need a good reason to head out. It’s no longer just “let’s catch a movie”. It has to be a theatre experience: Nolan film, IMAX, some massive visual spectacle. Even great films, like a clever romcom or a quiet drama, can get passed over because they don't scream "big screen."The Seasonality Problem

The film business is wildly unpredictable. Even with all the forecasting—budget size, star power, music, prior trends, no one really knows what will work. You can be methodical, analytical, even a little superstitious and still get it wrong. Then there’s timing: holidays, exam seasons, cricket, global pandemics. All of these throw a wrench in your beautifully crafted schedule. Just look at India. No one predicted that Tamil and Telugu films would dominate national box offices while Bollywood stumbled. That shift caught almost everyone off guard.Not Exactly Asset-Light

Running a theatre is not a small-capex game. You need prime real estate, big floor plans, high-end sound and projection systems, comfortable seating—and all of that adds up. For a company like PVR Inox, adding a single screen can cost upwards of ₹2.5 crore. So if you're adding a standard 5-screen multiplex, you're looking at ₹12–13 crore in upfront investment, before you even sell your first ticket.Battling Online Shoppers

Malls and movie theatres used to be the perfect combo. Shop, eat, watch a movie, repeat. But now? People are perfectly content shopping from their phones and ordering dinner in. Again, it’s not that malls are dying. In fact, many are evolving and thriving. But that easy footfall that theatres used to count on? It's not quite what it used to be.

It is worth noting though that even today, India doesn't have nearly enough multiplexes per capita when compared to giants like China or the U.S. However, this growth isn’t quite as organic as, say, air travel, where demand is more predictable and consistent.

The big issue with theatres, as mentioned above, is that movies are increasingly easier to access from home. So, to compete, theatres need to go beyond simply delivering the bare minimum. The experience they offer needs to be elevated. Companies like PVR Inox are known for their quality, but it may not be enough in the long run.

Imagine if different PVR Inox locations had their own unique vibe or atmosphere. For instance, one location could feature a small stall selling screenplays or memorabilia from legendary films. Another might lean into a retro aesthetic, or host themed nights for cult classics. Rather than feeling like identical branches of a corporate chain, each theatre could carry a bit of personality, like those charming standalone cinemas that cinephiles adore.

This way, they keep the operational and economic advantages of being a large chain, but introduce a personal touch that creates memorable experiences. It’s not just about watching a movie, it’s about where you’re watching it, and how it makes you feel.

All that said, I don’t think I’m particularly bullish on theatres. Of course, that doesn’t mean they won’t survive—they absolutely will. There’s a timeless charm to the big-screen experience: something communal, immersive, and emotional that’s hard to replicate at home. I’ll continue going to theatres as a customer, no doubt about that. But would I want to own one or invest in the business? Probably not. It’s a sector I enjoy from the seats, not the spreadsheets. (Yes super proud of that one)

Cover Image taken from Unsplash