The world in 2046

Trends for the future

I have absolutely no idea what is going to happen next month, which makes any attempt to imagine the world twenty years from now feel pretty ridiculous. Like deciding you’re ready for Wimbledon because you didn’t completely embarrass yourself at pickleball. And yet, I keep coming back to it. Thinking about the future, getting it wrong, feeling mildly embarrassed about having put the thought into words, and then doing it again anyway. So here we are. Again.

One thing does seem fairly obvious, though. The version of the world we are currently inhabiting is just one of many that could have happened. Things tipped this way rather than that, because of a handful of decisions, and an unhealthy amount of luck. If any of those had gone slightly differently, none of us would be reading or writing this. We would be somewhere else, worrying about something else, or not worrying at all. Which is a long winded way of saying that certainty is probably not our friend when talking about the past or the future. The future demands a probabilistic outlook.

When people talk about the future, there is one idea that always shows up early. The reset. The moment where everything breaks. A natural disaster, a catastrophic war, a government with an itchy trigger finger, or a fanatical belief taken too far. In that version of the future, the world does not gently improve or sensibly adjust. It snaps. And whatever comes next is something you cannot easily undo.

The appeal of the reset is that it is dramatic. It looks good on screen. Zombies, asteroids, unmistakable endings. You know exactly when things change. It gives history a restart point.

What is much harder to imagine, and hopefully much more likely, is a future that sneaks up on us. One that arrives through tiny decisions, dull incentives, habits we barely notice forming. The world almost never stops and announces that it has become something else. It just quietly does, while everyone is busy refreshing their phones or arguing about something unrelated.

With that in mind, what follows is not a prediction in the grand, prophetic sense. It is more like a set of guesses. Things that seem likely to happen if we avoid completely wrecking the place.

If the future is split into a hundred different paths, I would expect these ideas to show up in at least sixty of them. Not because they are exciting or inevitable, but because they are already happening. This is not about sudden transformation. It is about imagining a world where today’s slow moving trends have stopped being trends and started being assumptions.

Lets get to it.

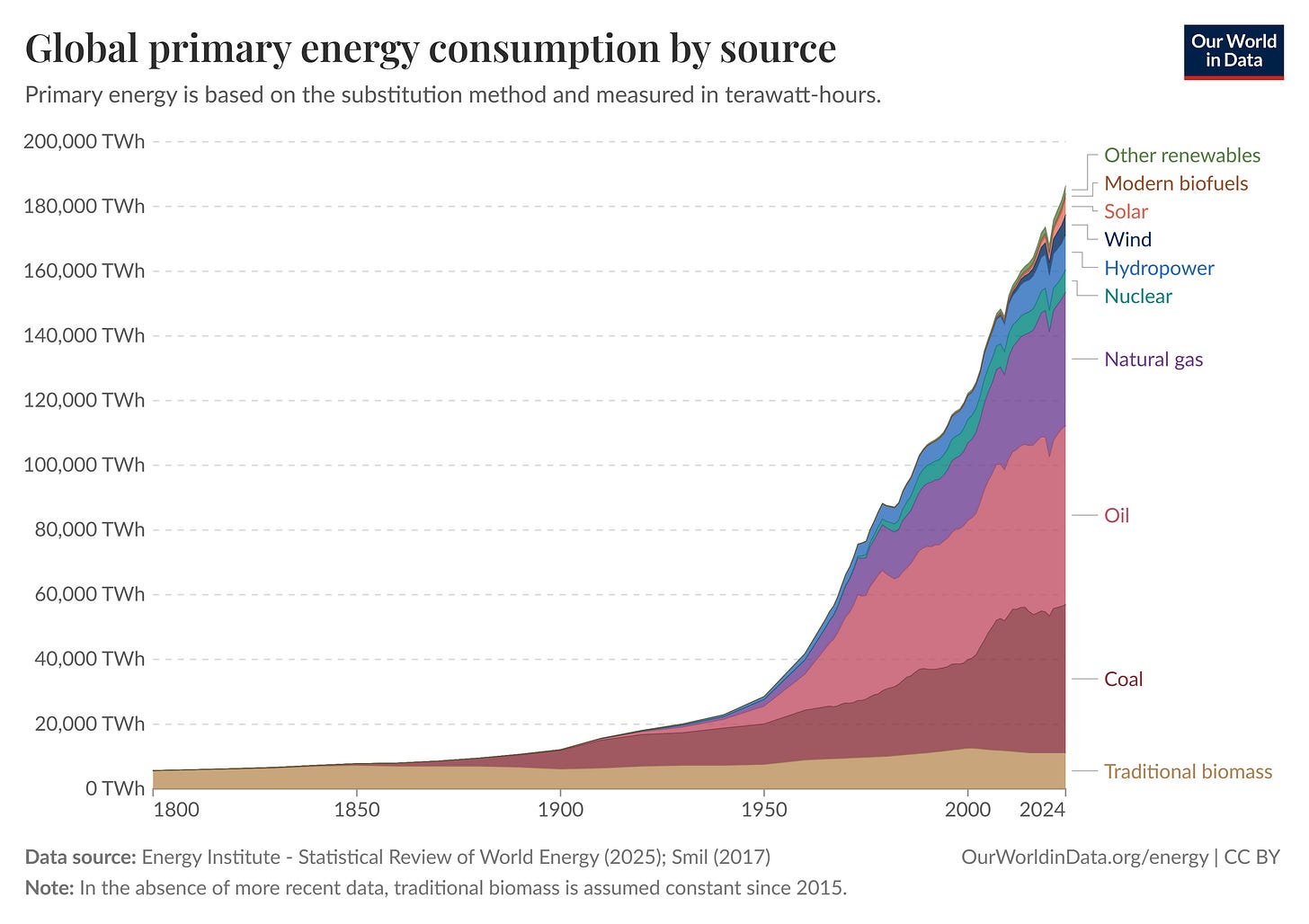

1. Dirty energy is not leaving the party

Every serious conversation about the future eventually trips over the same thing: energy. Not policy. Not good intentions. Not whatever shiny technology is making the papers. Energy. It’s the boring adult in the room. When energy is cheap and plentiful, societies get ambitious. Space programs. Megacities. Crypto. When it becomes expensive or unreliable, everyone suddenly rediscovers the beauty of restraint.

The transition toward cleaner energy does not change this reality. It complicates it. Clean energy reduces some dependencies, but it introduces others, from critical minerals to manufacturing capacity to grid stability. Even the things designed to save us are incredibly energy hungry. Wind turbines don’t grow on trees. Solar panels don’t arrive via good vibes. The steel, the concrete, the batteries, all of it requires enormous amounts of power. This isn’t a light switch moment. It’s a long, messy renovation where you keep discovering new structural issues behind the walls.

Then there’s the awkward bit. The countries that got rich by burning cheap fossil fuels now stand on the sidelines telling poorer countries to do it differently. Preferably cleaner. Preferably faster. Preferably without the same capital, technology, or institutional muscle. For most developing economies, energy access and growth still feel a lot more urgent than abstract climate targets set several conferences and time zones away.

Technology alone won’t fix this because culture has a vote, and culture is stubborn. Agriculture makes this painfully obvious. Livestock emissions matter, and yes, cows burp and fart their way into climate models. But asking entire societies to eat less beef isn’t a technical adjustment. It’s a social negotiation involving farmers, religion, income, and what people consider a proper meal. These are not small asks. These are arguments that last generations.

By 2046, energy unfortunately won’t be fully decarbonized. By 2056, probably still not. Fossil fuels will shrink, but they won’t politely exit the stage. Clean energy will grow, but unevenly, imperfectly, and with its own limitations. The future won’t look like a clean break from the past. It will look more like an awkward overlap, where old systems and new ones coexist, tolerate each other just enough, and occasionally get in each other’s way. Which, if we’re being honest, is how most transitions actually work.

2. The world after Globalization peaked

The modern world is far too complicated and far too intertwined to work without trade, capital moving around, and a lot of shared production. Resources are scattered unevenly. Skills are specialized to the point of absurdity. No serious economy can make everything it needs by itself, unless it is happy with a sharp decline in living standards and a long nostalgic phase. Integration, in some form, is unavoidable.

What is changing is not globalization itself, but what countries want from it and how much discomfort they are willing to tolerate in exchange for efficiency.

The first lesson was fragility.

Recent shocks exposed things we preferred not to look at too closely. Systems that were beautifully optimized in calm conditions behaved badly when stressed. When production runs that close to the edge, failure does not stay contained. It travels. Quickly. The very qualities that once made globalization feel elegant turned out to make it brittle.

By 2046, globalization is likely to feel more supervised. More selective. Countries will remain open where openness clearly helps growth and innovation, but they will want insulation or redundancies where failure carries real consequences. This is not a dramatic rejection of interdependence. It is more like a quiet admission that efficiency without resilience is a gamble, and not everyone is in the mood to keep betting.

The second lesson was Power.

Cersei Lannister put it bluntly in Game of Thrones when she said, “Power is power.” It does not come from participation alone, or from having read the right economic papers. It comes from capability. From having something tangible behind your intentions.

Not very long ago, manufacturing depth, industrial capacity, and control over critical technologies sounded like dry policy phrases. The sort of things people nodded at politely before changing the subject. Somewhere along the way, they stopped feeling abstract and started looking like survival traits. These are not theoretical advantages. They are leverage.

This becomes clearest in places where mistakes are expensive. Military capacity. Energy systems. Semiconductors. In these domains, dependence stops being a neutral condition and starts to feel uncomfortably like exposure.

Large economies with deep domestic markets can afford redundancy. They can decide when openness helps and when it hurts. Smaller economies do not have that luxury. They might have to specialize aggressively or accept a higher degree of vulnerability. In a more fragmented world, the ability to absorb shocks at home becomes a form of power in itself.

Fragility taught states what breaks. Power reminds them what holds.

3. Complaining about immigration is not going away

By 2046, immigration will still be one of the most argued about features of modern societies. Not because the economics are mysterious or unsettled, but because the trade off is unavoidable, and people generally dislike trade offs unless they are the ones benefiting immediately.

On paper, the case for immigration only gets stronger. Much of the world is getting older. Birth rates are falling across developed economies and, increasingly, across developing ones too. There are simply fewer young people turning up to do the work, pay the taxes, and quietly keep the whole thing afloat.

Fewer young workers means slower growth, weaker tax bases, and welfare systems that start to look uncomfortably like a promise no one knows how to keep. In purely economic terms, immigration isn’t a moral stance or a political preference. It’s a patch. One that keeps the system running longer than it otherwise would.

But economics is only half the story, and usually the quieter half.

I say this as someone instinctively sympathetic to the liberal case. The idea of plural societies drawing strength from different cultures, skills and histories is not something I find threatening. It is, in many ways, the ideal. But ideals do not cancel instinct. When growth slows, when jobs feel scarce, when housing tightens and wages stagnate, it is not surprising that people begin to notice who else is competing. Seeing someone who does not look or sound like you succeed in a constrained environment can trigger something older than policy. That reaction may be ungenerous. It may even be wrong. But it is not mysterious.

Part of the tension lies in how immigration is experienced. It is felt long before it is measured. It appears in neighborhoods before it appears in GDP figures. In accents, shop signs, schoolyards, waiting rooms. Even when integration works, and over time it often does, the transition is uneven. The disruption is immediate and local. The gains are diffuse and delayed. That gap is where resentment settles.

This is what makes the argument so stubborn. A country can genuinely need immigration to sustain growth, fund welfare systems and fill labour shortages, while parts of that same country struggle with the pace of change.

Technology complicates the picture further. As automation and artificial intelligence absorb more routine and even skilled work, demand for labour will shift rather than disappear. Care work, services and roles requiring physical presence will still rely on people. Manufacturing and clerical functions increasingly may not. Migration systems will become more selective, more skills focused, more transactional. That may improve efficiency. It will not remove controversy.

By 2046, complaining about immigration will not necessarily signal policy failure. It will signal that societies are still trying to reconcile what they require with what they are prepared to become.

4. Tottenham Hotspur will still not have won the league

Some predictions feel risky because they depend on technology, politics, or human behaviour, all of which have a nasty habit of changing their minds. Others feel safer because they depend on history, which, for better or worse, has a strong preference for repeating itself. Tottenham’s relationship with the Premier League falls firmly into the second category.

Every few years, the conditions seem right. There is a promising squad, young enough to feel exciting but experienced enough to feel serious. A tactically astute manager who says the correct things about process and patience. A season where rivals wobble just enough to create that dangerous feeling known as belief. This is usually the point where supporters begin to explain, carefully and at length, why this year is different.

And then, quietly and without much drama, something gives way. A mistimed tackle. A baffling substitution. A run of games where the ball refuses to bounce kindly. Nothing catastrophic. Just enough to remind everyone of why Tottenham is Tottenham.

By 2046, football will almost certainly look different. Analytics will be sharper. Money will be more global and more obscene. Players will be faster, fitter, and somehow still injured at the worst possible moments. But in a world defined by uncertainty, it is comforting to know that a few constants endure.

5. The monetary shrug

The global economic system currently runs on a kind of collective agreement that feels both powerful and slightly fragile.

Debt keeps rising. Not just household debt or corporate debt, but sovereign debt. Entire countries owe sums that would have sounded fictional a few decades ago. And yet markets mostly carry on. Bonds trade. Currencies fluctuate. Everyone refreshes their dashboards and goes to lunch.

At the center of it all sits the US dollar. The world’s reserve currency. The default language of global trade. Oil is priced in it. Debt is issued in it. Central banks hold it. For decades this arrangement has survived wars, recessions, political drama, and the occasional self inflicted crisis.

But here’s the uncomfortable bit. The system relies heavily on trust. Trust in US institutions. Trust in rule of law. Trust that political volatility remains theatre rather than structural failure. In recent years, that trust has been tested more openly than many would have preferred.

Would I be shocked if by 2046 the financial plumbing looks different? Not particularly. Reserve currencies have changed before. Systems evolve, sometimes gradually, sometimes because someone forces the issue.

Do I know what replaces it? Not even slightly.

A multipolar currency world? A patchwork of regional systems? Central bank digital currencies? Some hybrid arrangement we cannot yet name? All plausible. None obvious.

For now, we seem to be operating on the global equivalent of “if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it.” The dollar still works. Alternatives are either smaller, less trusted, or tied to political systems that make investors nervous. And when you are managing trillions, nervous is not a good feeling.

So the system continues. Heavily indebted. Occasionally wobbly. Remarkably resilient. A bit like that friend who insists they are fine while clearly running on caffeine and vibes.

By 2046, the architecture might look different. Or it might look almost the same, just slightly reinforced and quietly adjusted. If there is one safe bet, it is this: money will remain complicated, political, and slightly mysterious. And most of us will still pretend we understand it better than we actually do.

6. Healthcare stops being off the rack

For most of modern history, healthcare has worked like fast fashion.

You show up with a problem. The doctor reaches for the standard size. This drug. That dosage. This protocol. If it mostly fits, we call it success. If not, we tweak. It’s been remarkably effective, but it has always been statistical. You are treated as a representative sample of something.

By 2046, that approach may be changing.

The shift won’t be dramatic. It will creep in through watches that flag irregular heartbeats before you feel them. Sleep trackers that quietly log your bad decisions. Continuous glucose monitors. Smart homes that notice patterns. Affordable genetic sequencing that tells you not who you are, but what your cells are inclined to attempt.

The body is becoming measurable.

Healthcare begins moving away from averages and toward probabilities attached to you specifically. Not a general response to a drug, but your likely response based on genetics, metabolism, history. Medicine starts to look less like fast fashion and more like tailoring.

Tailoring requires measurements. And someone has to hold those measurements somewhere.

Which brings us to the awkward part: the data.

Health data may become the most valuable and most sensitive asset many people own. Insurance companies, whose entire business is pricing uncertainty, will find this hard to ignore.

The more precisely risk can be measured, the harder it becomes to pretend we are all roughly the same. Do we want insurance priced according to our biology? Or according to a broader idea of shared risk?

Personalized medicine promises earlier detection, fewer surprises, treatment plans that adjust before things break. That’s the optimistic version. The other conversation is about ownership, consent, and whether opting out of measurement becomes its own kind of red flag.

By 2046, ignorance is unlikely to make a comeback. The devices are too useful, the incentives too aligned. We might see a quiet normalization of living in ongoing negotiation with our own biology.

7. The AI chaos

I have no freaking idea what AI is going to do. It can already do a frightening amount of what lawyers, accountants, and financial analysts spend their days pretending to do. Some of it is terrifying. Some of it is amazing. All of it is going to feel faster than anyone can comfortably process. I am already learning how to make pizza, in case no jobs exist and I have to open a small restaurant to pay the bills.

This is exactly the kind of period futurist Alvin Toffler described as future shock, the disorientation that happens when change moves faster than we can absorb it. Old habits will falter. Institutions will stumble. Some systems may break. Society may feel dizzyed, anxious, and uncertain. For the next twenty years we are likely to experience that full on “hold on to your hat” dissonance.

But history offers a little hope. When personal computers first arrived, they felt like a tidal wave. (I’m told) Offices scrambled, schools panicked, people wondered how these machines could possibly fit into daily life. Within a couple of decades that shock faded. Computers became ordinary. Social media and smartphones went through the same cycle, first overwhelming, then mundane. The panic does not disappear entirely, but the world adjusts. We adapt.

By 2046 the dust should have settled a bit. AI will be everywhere, still powerful, still shaping work, life, and culture. But it will probably feel less like a tidal wave and more like background infrastructure, something you notice only when it does not work, like electricity or GPS. The headlines will exist, the breakthroughs will exist, but the chaos will feel like history, something we hopefully survived and integrated into our lives.

Or, of course, the other possibility is the Dune option: we remove all AI and hope humanity survives. For now, I’ll stay hopeful and keep practicing my pizza.

8. Inequality

So much of what I’ve written so far, the health tracking, the personalized medicine, the AI chaos, might sound exciting or terrifying depending on your temperament. But let’s be honest, most of it is abstract and not for everyone. Poverty is not going to disappear. Hopefully it eases, but wherever there are shiny new toys, inequality will probably follow.

We’ll have smarter homes and treatments tailored to our biology. Meanwhile, in the same cities, towns, and villages, people will still be juggling basic survival: clean water, reliable electricity, decent food. Access to healthcare, education, and even advanced AI assistants will still be wildly uneven. For some, the future will feel dazzling; for others, barely changed from today. Geography, income, and opportunity will shape how anyone experiences progress.

And then there is gene editing. Humans tinkering with DNA is not science fiction anymore. Ethical dilemmas will multiply. Could we see genetically superior humans? Not entirely out of the question. And yes, that reality will sit right next to people who have none of these advantages. Schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods will be caught in the friction. Social tensions, envy, and resentment could grow, even as technology races ahead.

AI adds another layer. Some jobs will vanish; others will transform. Some people will thrive with AI as a tool, while others may find themselves sidelined, struggling to adapt in ways that no algorithm can fully prepare them for.

By 2046, some of the world will feel astonishing, and some of it will feel painfully familiar. The gap between the two will probably matter more than all the progress itself. Convenience, personalization, and digital brilliance will coexist with stubborn old problems that no algorithm will ever fix.

9. The human touch is here to stay

The world will be smoother in 2046, for those who have resources. In many ways, this is progress. Fewer queues. Fewer wasted minutes. Fewer obvious mistakes. But something interesting happens when everything becomes optimized. You start to miss the rough edges.

Take marathons.

Yes, the shoes are absurdly technical. Yes, your watch will record every heartbeat, stride, and flinch. Yes, the whole thing will be uploaded to Strava. And yet none of that is really the point.

Here is an event where thousands of people wake up before dawn, to run 42.2 kilometers for no practical reason at all. What’s more, they pay for the privilege. They voluntarily experience discomfort, and then celebrate it together.

It is inefficient. It is irrational. It is profoundly human.

And afterwards, no one gathers around to compare recovery scores. They gather to replay the moment they almost quit at kilometer 34. The stranger who shouted their name. The runner who finished with their 1 year old daughter, in their arms. The shared stupidity of having done something so difficult.

Technology is there, sure. But it doesn’t define why they show up. The reason is emotional. Stubbornly emotional. The need to struggle. To be seen. To belong. That instinct predates GPS watches and Strava streaks.

As homes become smarter and entertainment more personalized, the value of places that feel unmistakably human quietly rises. Not because they are efficient. But because they aren’t.

Gyms where the machines wobble and the trainer calls you by the nickname only they know. Small restaurants where the menu changes because the owner felt like it. Bookshops arranged by taste rather than algorithm. Bars with uneven tables and conversations that drift.

Places shaped by preference, not optimization. Technology will still be there. But the reason people show up will not be efficiency. It will be texture. Warmth. The small relief of being somewhere that hasn’t been fully optimized.

By 2046, life may feel increasingly mediated by systems that anticipate our needs. Convenient, yes. Useful, certainly. But occasionally flattening. Here’s to the places that are messy, opinionated, alive, and stubbornly human.

Many of these thoughts are borrowed rather than invented. They come from reading people who think in systems, constraints, and probabilities. That includes Tim Urban, Alvin Toffler, Nassim Taleb, Ray Dalio, Vaclav Smil, Charlie Munger, and many others. I recommend all their work.

If you made it this far, thank you. Hopefully some of it made sense and not all of it was stupid. Thanks for reading!

Cover image taken from Unsplash.